Out of the many advantages of microservices, the most significant motivations are scale and autonomy for business units. These go hand in hand. However, we still need to create an integrated experience that makes sense for the end user. It’s important to keep both these aims in mind when developing strategies for the interactions between microservices. Those are the strategies that can make or break your effort.

How we map each microservice determines how autonomous it will be. Microservices modeled by bounded contexts [1] or business capabilities are more natural to the autonomy than the ones based on the technical abilities. Let's consider the example of a banking application. Some bounded contexts a typical it can have are Login and Security, Profile Management, Transaction Services (one service for debit and credit because they are closely tied), Spending Reports, and external services such as Credit Report Check or Rewards Check. These contexts may have many technical implementations that are similar: for example, logging. However, if we create logging as its own service, almost all of the other services are going to be dependent on it. It can become a linchpin: You take that down, and the business stops. Instead, we can push the logging implementation into a library, create services based on the contexts, and make use of the logging library if possible.

Mapping services in vertical business slices with their own databases is only the beginning. We still need to integrate them in a way that creates a cohesive experience and share the data between those services. How do we achieve this while maintaining the autonomy? Before we look into how we could integrate, we must first assess the myriad of interactions between individual services that will influence our integration decisions.

Creating loose coupling and high cohesion

To ensure autonomy and scale, individual services should be highly cohesive (grouping similar functionalities) and loosely coupled [2]. “Coupling” in computer science describes the interdependence between modules [3]. The loosely coupled systems share well-defined data in the form of messages, and that’s all. They don’t worry about states, uptimes, performance levels, or technical implementations.

From our banking example, if credit and debit services are separate, they become very dependent on each other because they tend to affect the same data piece: your account balance. If there’s a discrepancy between balances shown, which one is right? These services must be incredibly consistent, which results in a lot of back and forth network chatter. Instead, we can merge these two functionalities into one cohesive service and avoid the complexity.

Iterating business boundaries

Services that depend too much on other services’ data, implementations, and uptimes, could be a symptom of wrong or outdated business boundaries. Businesses always change, which is why we need to revisit boundary assumptions periodically. This ensures we aren’t creating too fine-grained services, i.e., nanoservices [4]. These nanoservices tend to have fragmented logic and poor performance. They add a lot of maintenance overhead. Horizontal services that are based on technical implementation rather than business boundaries fall into this pit. The division of credit and debit functionalities into their own services fits this, too. There is no need to break the cohesion and introduce a network between them. What’s wrong with the network?

Knowing the network limitations

If there is a chance of something breaking down, we need to have a plan to deal with it as a good engineering practice. Communication over the network is a prime example of it [5]. Services across the business boundaries connect with each other over the network. We need to understand the impact of this because very little can be in the maintenance team’s control outside of the business boundary. Hence, we should keep the network communication as minimum as possible. For example, in the banking application, we need to let the Spending Report service know of a debit transaction. An incorrect implementation would have a call to that service asking if such operation is possible or maybe perform validation on the input parameters followed by the actual reporting of the balance change. These two can be easily merged into one cutting the chatter by half. This idea is based on the Tell, Don’t Ask principle [6]. All of this may seem small, but these little things add up quickly. It is essential to understand the implications of putting APIs on HTTP.

Having a contract-oriented mindset

It’s important to think about the consumer of your API all of the time, no matter which kind of integration we decide to go with. The code written with the service’s consumer in mind has better encapsulation and hides the implementation details very well. Test-driven development can be helpful in this regard. With TDD, we can write on consumer contracts first and then code to satisfies those contracts. PACT[7] can help us share these contracts between services.

It becomes tough to draw boundaries in the code that’s not written this way, for example, CRUD or repository pattern based APIs. They are concerned with the database entities. They span across business functionalities producing tighter coupling. At that point, redesigning them first is a better idea.

Understanding CAP theorem and database technologies

The primary goal of distributed systems is to scale better. In an ideal world, the data shared by loosely coupled services could be replicated without any trouble. That would require optimal consistency, availability, and partition tolerance, which means 1) every reader gets the latest write, 2) every request receives a non-error response, and 3) because the network separates microservices, they must be about to handle an arbitrary number of messages getting dropped. However, this is restricted by the CAP theorem [8], which states that only two of these three conditions can be optimally met in any system.

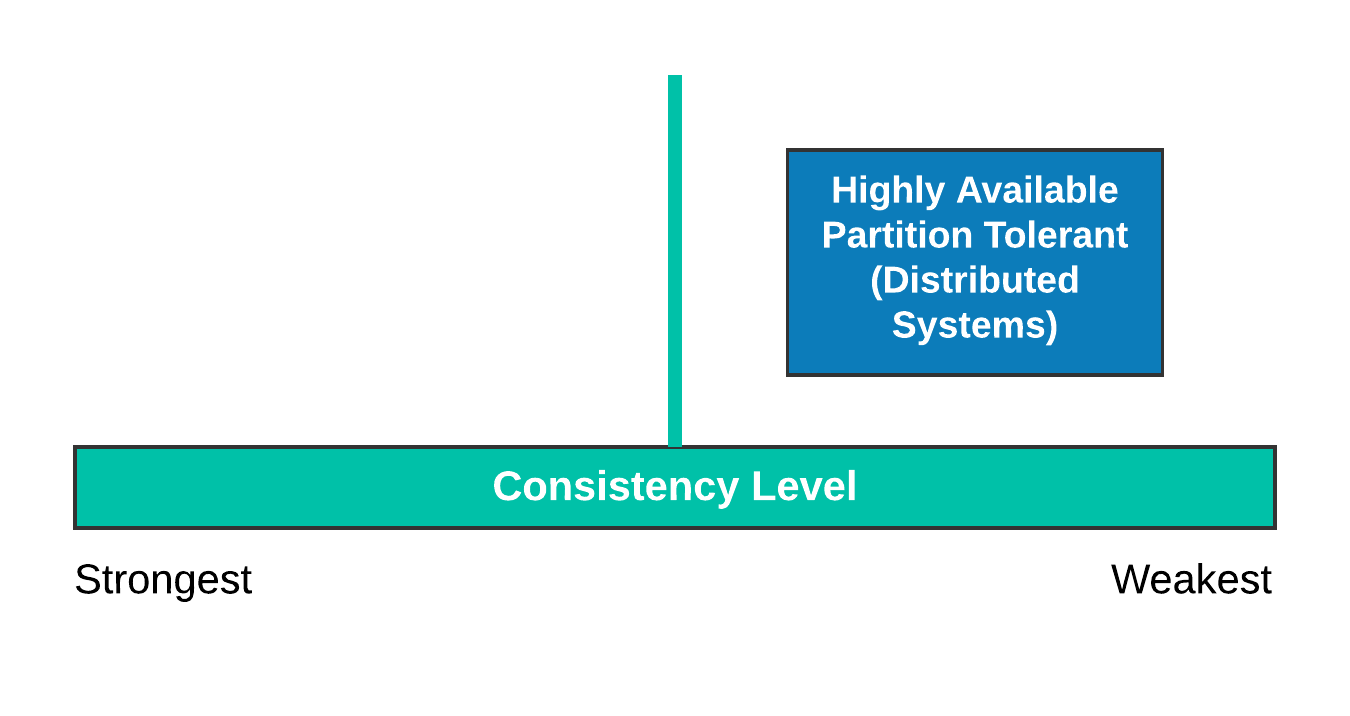

Because availability and partition tolerance are critical in the distributed world; we must deal with weaker consistency, as shown below:

However, consistency itself has many levels. Distributed database technologies such as Azure Cosmos DB supports five of them [9]. Google Cloud Spanner technology, on the other hand, is challenging the CAP theorem by claiming to offer high consistency along with availability and partition tolerance [10]. We need to keep these conditions in mind while deciding on database technologies for our systems.

Understanding transactions and transactional boundaries

Distributed transactions across multiple services are hard to get right because they go through multiple phases before the data is committed [11]. They require orchestration that makes the systems very fragile. All of this hassle to get to a place which can’t scale well and the database choices may differ between services. Now what?

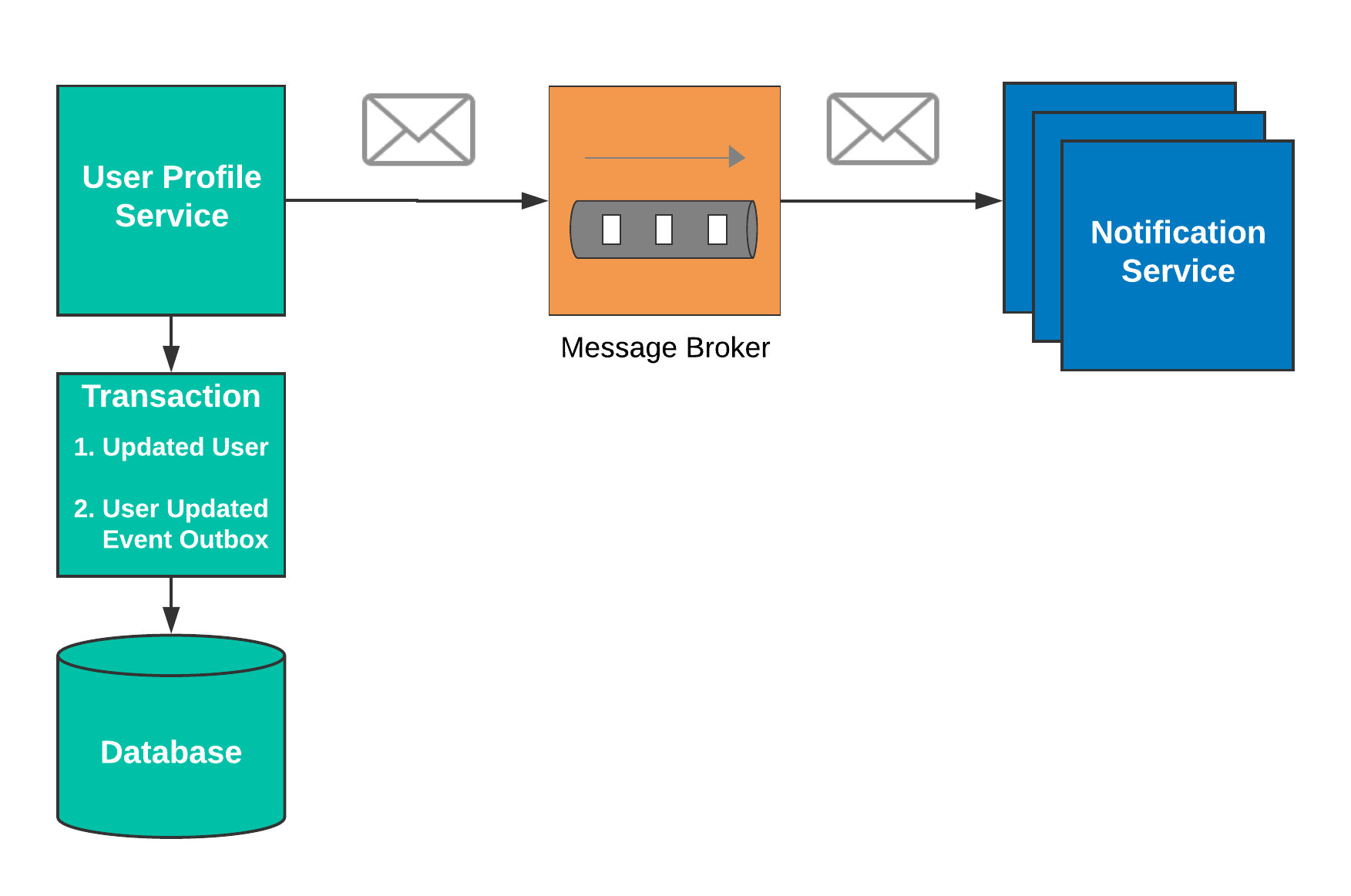

Instead, we can let new database technologies such as Cosmos DB or Cloud Spanner handle the complexity behind the scenes. If that’s not an option, we can support transactional guarantees within the service boundary and generate events with Outbox pattern for everyone else to consume [12]. Using our banking example, when a user changes his or her phone number in the profile, we can commit that info in the User Profile service’s own data store and generate events for the other systems to consume. After the successful consumption of that message, our Notification service can notify the user for account changes, as shown below:

Being careful with synchronous (blocking) APIs

We must consider the limitations of our networks before putting services there. Synchronous calls across services usually take place over HTTP, which can become very tricky to manage What happens if the HTTP service goes down? How do we know it’s down? How do we handle the failures? How can we rollback synchronously applied changes? Where does the cache live? How many types of caches will be managed? One per consumer? One per call? All this complexity can result in a complex architecture, with everyone calling each other.

Synchronous services have higher expectations on response times, making them more challenging to scale and maintain. Less is more here. Synchronous API calls usually lead to more orchestrated solutions. Sometimes we need physical obstacles to prevent incorrect usages from creeping into the systems [13]. What’s wrong with the orchestration? What can we do instead?

Considering choreography over orchestration

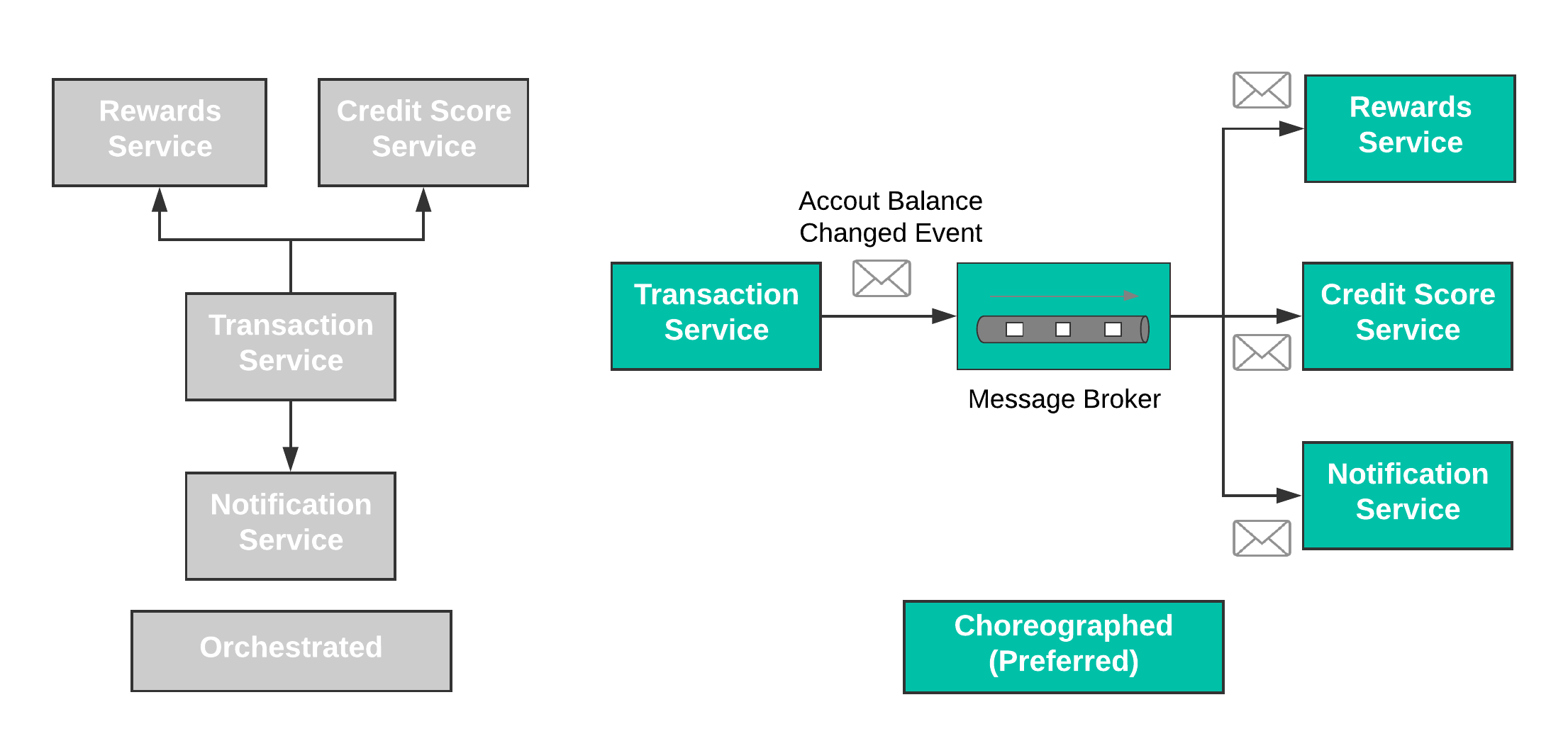

Any system that requires a lot of central management or any service that plays a role of that kind can become problematic. They become too important to go down. Everything is funneled through them, increasing the coupling in the system. This highly coordinated approach is known as orchestration. In contrast, a choreographed approach lets services decide what to do when an event happens. These services don’t need handholding from a central manager. Back to the banking application example: upon debiting money from your account, the Transactions service can call the Rewards services, which can call the Credit Score service, and end it with a notification. In this case, the Transaction service is sitting in the middle of everything playing a traffic cop. Instead, it can just create an “account balance changed” event and let other services subscribe to those events and finish their operations independently. The latter is a much more decoupled approach—a notification can still be sent even if the credit score service is down.

A choreographed approach can be the difference between partial outage vs. full outage, making the services themselves more robust [14].

Tying it all together

Considering your services structure and the complex web of interactions they inherit is the first step to building a robust microservices architecture. There are no silver bullets in software engineering, but each of these principles is a building block in the construction of a full understanding of the interactions between services. In the next part of this series, we will take a look at the types of integrations we can implement to create cohesion within your systems, and for your end users.

References

[1] More on bounded contexts

[2] Service definition from SOA patterns book

[3] This article does an excellent job explaining different levels of coupling

[4] More on the nanoservices antipattern

[5] Read about the fallacies of network computing

[6] The "Tell, don’t ask principle" explained with C# example

[7] Details on PACT

[8] CAP Theorem explained

[9] Consistency levels supported by Azure Cosmos DB

[10] Google Cloud Spanner

[11] Distributed transactions two-phase commit protocol

[12] Learn about Outbox Pattern

[13] Hear Eric Evans’ argument for physical separation of services in his GOTO Conference talk

[14] The routing slip pattern for messaging can also lead to more choreographed solutions

And to learn more about dealing with the fallacies of network computing in distributed systems, check out this video from Headspring's Chief Architect Jimmy Bogard: Building Distributed Systems.

(This is a cross post from my post on Headspring's blog)

Comments